Andy Brogan shares some initial responses to his involvement in the project.

I was first invited to join the DEMO:DRAM project on the basis of my background in political theory and critical pedagogy, so that seems a good starting point for my first blog post. Throughout my MA and PhD I’ve worked on the connections between the role of democracy in classrooms, democratic awareness and student civic engagement, ideas which sit at the heart of DEMO:DRAM and which I’ll work through in more detail here.

Paulo Freire’s seminal work Pedagogy of the Oppressed was the starting point for the broader field of critical pedagogy. Freire began with a critique of traditional methods of education, characterising traditional approaches as ‘banking’ in which the teacher takes the role of an active subject who fills the passive students with knowledge. In this educational approach students are not taught to think, create, and question knowledge, but are taught to unquestionably accept the knowledge gifted to them by the knowledgeable teacher.

Paulo Freire’s seminal work Pedagogy of the Oppressed was the starting point for the broader field of critical pedagogy. Freire began with a critique of traditional methods of education, characterising traditional approaches as ‘banking’ in which the teacher takes the role of an active subject who fills the passive students with knowledge. In this educational approach students are not taught to think, create, and question knowledge, but are taught to unquestionably accept the knowledge gifted to them by the knowledgeable teacher.

Placing this critique in the larger social context, Freire argues that in this educational system the students are actively prevented from considering their own position in the world and the role they can play in shaping the world around them. Instead of engaging students in a process of knowledge creation and self-affirmation, the banking model of education holds students in a position of oppression.

In response to this traditional approach Freire proposed an alternative, critical pedagogy. At the heart of critical pedagogy is the emancipation of students through involving them in the process of knowledge creation and creating the space and conditions for them to pursue their self-affirmation. Critical pedagogy aims to empower students and teachers alike by bringing critical thinking to the fore. Freire argues that, through critical thinking, students can come to see themselves as actors in the world around them rather than passive objects of systems beyond their control. Critical pedagogy starts from the immediate world of the students and draws on this for its material, and by posing questions about the community in which the students live Freire argues students are able to gain a critical distance to their everyday life and are better able to consider the active roles they play in their community and society at large.

Through engaging in processes of critical thinking students are able to recognise the role they have already played in the creation of the world in the past, how they continue to play this role in the present, and as such, how they are in a powerful positions to carry this role into the future. This interplay between action and reflection on action takes us to a central notion of critical pedagogy, praxis: the ongoing relationship between taking action and critically reflecting on the action taken to inform future action. By entering the process of praxis students come to see the world as an arena they are able to shape and transform through their thought and action, and as such the critical pedagogy proposed by Freire becomes a vehicle for social change.

This different approach to education brings with it a different student-teacher relationship: one which focuses on communication and dialogue between teachers and students. Critical pedagogy requires the teacher to engage in an ongoing effort to communicate with the students about the world around them, fundamentally shifting the understanding of knowledge to a collaborative and co-creative basis. By engaging in dialogue with students to enhance their critical thinking and self-affirmation the ‘teacher-of-the-students and the students-of-the-teacher cease to exist’ (Freire, 1993, 61) and in their place arise new terms, ‘teacher-student’ and ‘student-teacher’ (Freire, 1993, 61).

For Freire this realignment of teachers and students works for the benefit of all through dramatic social change. This social change occurs through greater teacher and student engagement with all aspects of social and political life, from community groups, to unions, to organised political parties. It is this notion which sits at the heart of all the shades of critical pedagogy to come in the decades which followed the release of Pedagogy of the Oppressed: education is political, and education can help to change the world for the better through greater justice, equality, democracy, and freedom.

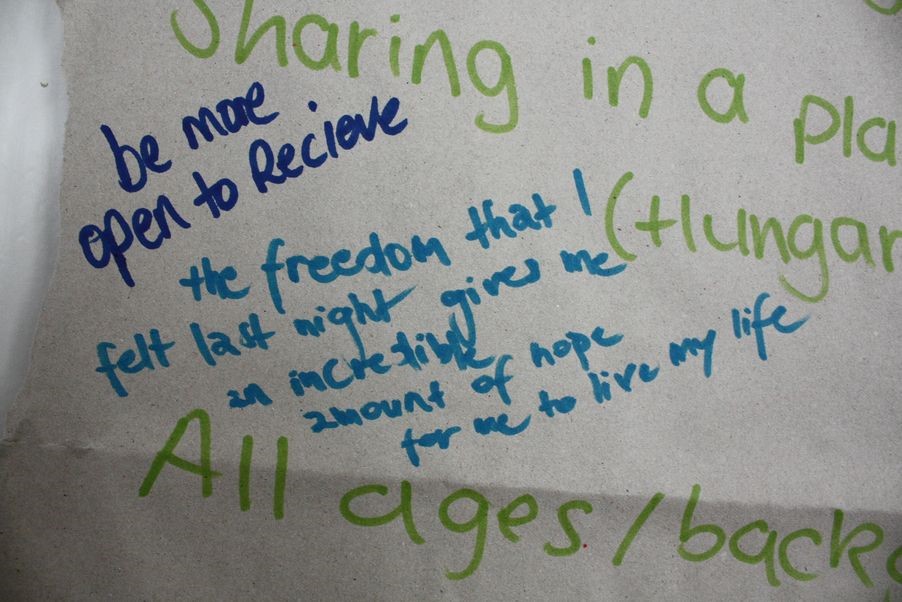

So what of the connection to the DEMO:DRAM project? In the initial project application DEMO:DRAM identified a number of pressing issues in European education, including the disengagement of young people from the issues and processes which impact their lives. Critical pedagogy’s focus on the context of the students and the development of student civic engagement as a vital element in a functioning democracy offers a theoretical grounding for the DEMO:DRAM project. In addition to this, the change in relationship between student and teacher echoes the attempts of the DEMO:DRAM team to offer innovative ways for arts and humanities teachers across Europe to engage in dialogue with their students. As with critical pedagogy, practices of teaching and learning geared towards passing exams are not sufficient to address the democratic awareness of students, student civic engagement, and the role of democracy in the classroom and beyond.

My first conversations with colleagues about the nascent project struck a chord with what I already knew about critical pedagogy, but brought to the fore something which had until then been at the periphery of my work: drama and theatre. A close friend is a dramaturge and play-write, another wrote an MA dissertation on Augusto Boal, the Brazilian theatre practitioner inspired by Freire’s work, and here was a project offering me the chance to engage with the connections between drama in education and democracy in a more structured way. I jumped at the chance.

While this post has primarily focussed on critical pedagogy my hope is that it acts as an introduction to me and my interest in the project, as well as adding another dimension to the work the project is undertaking. It also acts as a launch pad for future pieces in which I can give a greater account of the form of democracy sought in critical pedagogy, and by extension, DEMO:DRAM, and offers the chance to draw out the connection between critical pedagogy and dramatic practices as pursued in DEMO:DRAM.